Good morning!

This is about to be a very self-promotional intro. I apologize in advance, but there are two things I’d like to share.

First, I recently started contributing to another newsletter. (I love newsletters!) This one is for Gayjoy. Subscribe for a weekly dose of queer pop culture, plus a roundup of fun gay stuff happening in NYC.

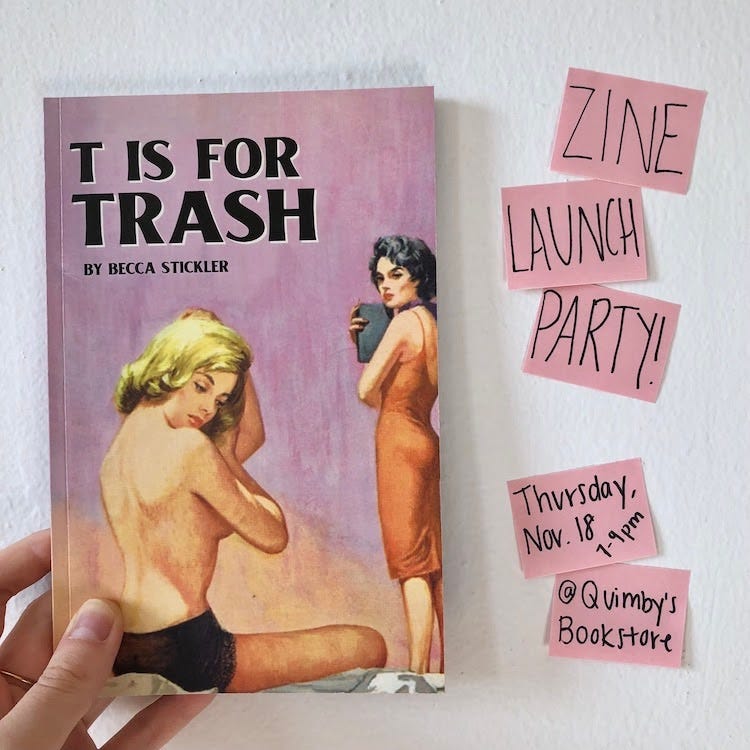

Second, the T is for Trash launch party is tonight at Quimby’s Bookstore in Williamsburg.

Whether you’ve already purchased a zine or not, I’d love to see you there! I’ll be at the bookstore hanging out and pouring drinks from 7-9pm, then may or may not get a group together to head to a nearby bar after.

See you later!

— Becca

The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi

Fiction, 2020

Death is often near the conclusion of a novel, but this one gets into it from the very first line:

They burned down the market on the day Vivek Oji died.

And though the author slowly builds towards revealing the circumstances of Vivek’s death, it would be misleading to call this story a mystery. It’s more of a gradual unfolding of Vivek’s life, and of the parts of him that other people either saw or chose not to see.

Growing up in Nigeria, Vivek is surrounded by the other children of “Nigerwives,” immigrant women who’ve married and started families with Nigerian men. But he’s a mystery to those around him even within this tight-knit community of outsiders, occasionally slipping into fugue states that seem to fully disconnect him from the world.

The only person who seems to come close to understanding him as a child is his cousin, Osita. But even he only allows himself glimpses of Vivek:

Picture: the boy, shirtless, placing necklaces against his chest, draping them over his silver chain, clipping his ears with gold earrings, his hair tumbling over his shoulders ... Osita wished, much later, that he’d told Vivek the truth then, that he was so beautiful it made the air around him dull.

Rather than embracing Vivek’s exploration of beauty, he snaps at him to remove the jewelry before he gets caught. Later, when Vivek’s parents pull him out of college because of concerns over his mental health, Osita sees him for the first time in years and is shocked to see his cousin with long, feminine hair.

Meanwhile, Vivek’s mother Kavita treats him with measured tenderness, brushing his growing hair and smoothing it with coconut oil—but dismissing any suggestion that he might be queer with revulsion.

It’s through these shifting perspectives that we see many of the people in Vivek’s life love him without fully understanding him. And after his death, we see them grapple with the reality that they may never have known who he really was.

But as readers, we’re given small glimpses of the true Vivek in the form of missives from beyond the grave:

I didn’t have the mouth to put it into words, to say what was wrong, to change the things I felt I needed to change. And every day it was difficult, walking around and knowing that people saw me one way, knowing that they were wrong, so completely wrong, that the real me was invisible to them.

These glimpses are few and far between enough that they feel almost startling, like being let in on secrets we’re lucky to know. But naturally, Vivek isn’t the only one with secrets.

***SPOILERS AHEAD***

I normally shy away from spoilers, but I find it odd that many rave reviews of this book (an instant NYT bestseller last year!) leave out the fact that an incestuous relationship is a major part of the story. It made me quite uncomfy to read, but it seems like that was kind of Emezi’s goal.

In an interview with Rivers Solomon, they explain that they’re interested in writing “deviant” relationships, and exploring how people respond when confronted with things that challenge their morals:

It’s not about the story, it’s about the reaction within the person who’s receiving the story. And I’m interested in the way that writing deviance challenges people’s experience of themselves—in terms of what they would’ve thought was okay, and what it brings up for people.

I also went down several Goodreads comment threads (spoilers in that link) in which readers argue about the morality of certain types of incest, citing the fact that it’s legal in many countries, including Nigeria. I personally feel fine about remaining grossed out by it.

Despite the incest (what a phrase!), it’s a gorgeous story. And if your book club is reading it anytime soon, the discussion is guaranteed to be lively. Invite me!

Queer points:

+3 for a poster collection including Missy Elliott, En Vogue, and Backstreet Boys

+6 for a friend group made up almost entirely of bisexuals

Buy it on Bookshop