What are your feelings re: Halloween?

I have not historically been a huge fan (I have an embarrassing and paralyzing fear of masks), but this year I’m finding a lot of joy in taking evening walks around my neighborhood, admiring my neighbors’ collections of pumpkins and skeletons and fake cobwebs.

It also helps that unlike the Octobers of my childhood, the temperatures have been in the 60s and 70s in Brooklyn all week. I try not to think about the fact that this is only because our planet is slowly warming to uninhabitable temperatures, which is arguably scarier than the giant clown that’s taken up residence in a Henry Street alley.

Anyway, in the spirit of the season, I’d like to recommend a horror trilogy—something that will likely never happen again, as long as this newsletter may live. If you’re even remotely active on gay stan corners of the internet, you probably already know that it’s going to be Fear Street. If not, I’d be delighted to fill you in.

The Fear Street trilogy kicks off in 1994, with an opening scene that’s a direct homage to the original 1996 Scream. The rest of the movie feels a lot like a classic 90s slasher flick, except 1) there’s a curse behind the killings and 2) there are lesbians.

In a fun twist, the lesbians are the leads, rather than side characters who have sex and then die. They’re central to the story for all three films, even as the second jumps back in time for a bloody summer camp killing spree in 1978, and the third goes even farther back to unveil the roots of the aforementioned curse in 1666.

Parts are a bit gory, and Alanna and I slept with the lights on for a few nights after the second and third movies, despite intentionally watching them in broad daylight. But your mileage may vary, as we are both quite wimpy.

— Becca

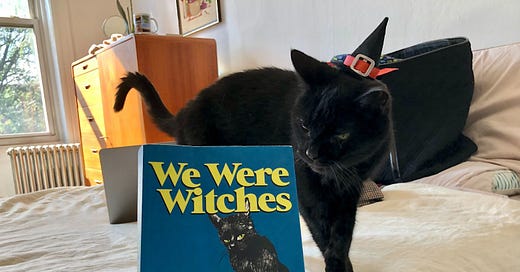

We Were Witches by Ariel Gore

Fiction, 2017

Growing up in a conservative, christian community in the 90s and early 2000s, I understood early on that teen pregnancy was shameful. I remember being taught the statistics in health class about how having a baby as a teenager set that baby up for lifelong failure, and I remember learning in church that sex before marriage, generally, was disgusting. The latter involved an exercise in which each member of my preteen youth group put unwrapped Hershey’s Kisses in our mouths, then spit the gooey, dissolved lumps of chocolate into our hands. Would any of us want to eat the others’ candy now that it was a saliva-laden mess?

It was all a metaphor, of course, for our genitals, which would inexplicably be rendered inedible following sex. Now, add a baby to the mix? Our entire lives would be ruined—though that part only applied to the girls. And that much was clear even outside the church, thanks to countless nationwide ad campaigns throughout my teenage years that branded young moms as a blight on society.

This attitude towards sexuality serves as the backdrop to Ariel Gore’s We Were Witches. Part novel, part memoir, it tells the story of a teen mom trying to get a college education, while everyone (from the school’s administrators to her judgmental neighbors to the entire court system) seems dead set on standing in her way.

When Ariel’s family finds out that she’s pregnant at 18, their reaction is shame—shame that they expect her to feel, too. And rather than offering any form of support, they want her to take that shame and disappear. They’d also really like for her to stop insisting she’s a lesbian, which is almost as shameful as the whole teen mom thing.

But as she works her way through college and warms up to feminist texts (after initially dismissing them because “feminists just get abortions”), Ariel gradually rejects that shame and begins to figure out what it would mean to become the writer of her own story:

Maybe I could rewrite the fairy tale of my life, transforming every blow to the head, and every cut to the cunt, and every crucified doll into some kind of an initiation.

Maybe this could be my new genre: the memoirist’s novel. My words could form a magical spell, like an alchemical furnace, built with the conscious intention of transmuting shame into power.

And the spells she mentions here aren’t the only magic in the story. Ariel occasionally practices spells to keep her daughter safe, to set her intentions, and to attract money when she needs it. She also receives visits from powerful women, both dead and alive, fictional and otherwise, that help her reclaim her power. After being treated callously by her doctor and boyfriend following her daughter’s birth, for example, she writes:

Artemis appears—head of a goddess, body of a deer—a day late, shooting arrows into the necks of the doctor and my boyfriend. They both fall, bleeding from their jugulars…. I gesture toward the fallen men as Artemis rides on.

It’s a story of empowerment, yes, but it’s also a story of rage. It’s a story of how consistently and intentionally our systems demonize and punish young mothers, single mothers, and queer mothers, and especially women who fall into all three of those categories. And somewhere in there, it’s a story of healing—through magic, sexuality, and a stubborn insistence on surviving.

Queer points:

+8 for references to Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Pat Califia, Cherríe Moraga, Judith Butler, bell hooks, Leslie Feinberg, and Jeanette Winterson (among others)

+21 for a scene in which Ariel gets matching snake tattoos with her ex-girlfriend

Buy it on Bookshop

Oooh! Adding to my TBR. Have you read We Ride Upon Sticks? It's weird and witchy and queer and I love it.